Some de-essers feature a function that allows you to hear only what the processor is doing, which can be helpful for determining if the de-esser is working at the correct area of the frequency spectrum. I suggest experimenting with both when mixing, and discovering which works best for the specific performance. Split-band will attenuate a smaller range of the frequency spectrum, generally the high frequencies where sibilance occurs. It will attenuate all areas of the frequency spectrum evenly. Wide-band is great for general de-essing tasks and is a great starting point. I’ve found lookahead to be helpful when mixing several Hip-Hop projects.

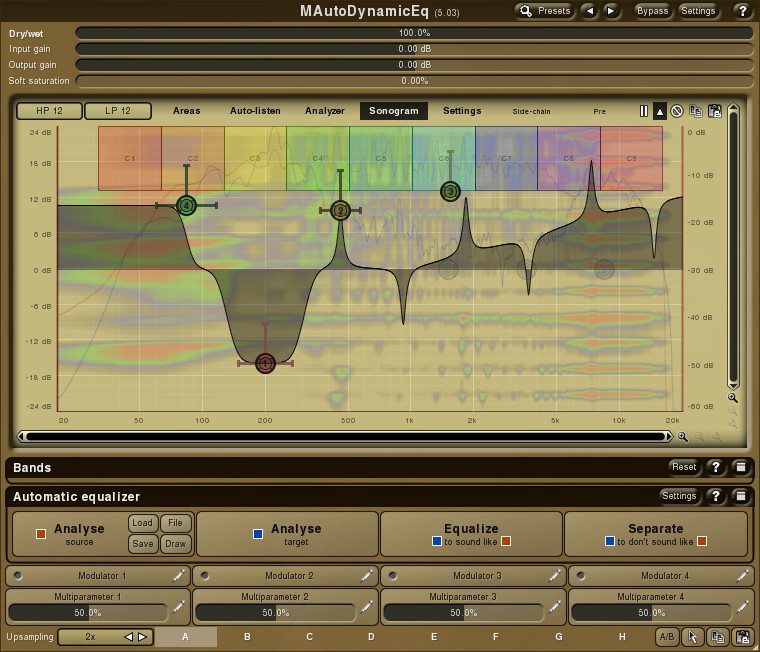

For rapid-fire vocal performances, this might be a useful feature to handle sibilance. This feature allows the de-esser to predict incoming sibilance by “looking ahead” a certain amount of milliseconds. Higher values can create undesired artifacts and sometimes leave the vocalist sounding “lispy” Lookahead Lower values may sound more subtle and natural but might not do the job entirely. This determines how much de-essing will take place once the amplitude crosses the threshold. Once the amplitude of the signal “crosses” the threshold, de-essing will occur. Much like the threshold control on a compressor, this determines the point at which the processing takes place. De-Esser Controls and Terminology Threshold I want to be careful to clarify that not all of these are designed specifically for the task of de-essing, but plugins have come such a long way in a short time, and several of these handle sibilance brilliantly. Once the de-esser detects that the amplitude has surpassed a set threshold, attenuation occurs.īeneath is a breakdown of some of the terminology you’ll typically find on a de-esser and a roundup of my favorite plugins used for de-essing. Traditionally, a de-esser works as a compressor that has been fed an EQ boost via a sidechain, making it more responsive to the frequency range at which the EQ boost has been applied. There isn’t a singular solution to this issue, but a “de-esser” is one of the most common tools used to tame harshness in vocals.

Ideally, the recording engineer will get it right at the source, but in some cases, the mix engineer simply has to make do with what they’ve been provided - moreover, with modern music production and mixing aesthetics tending to call for liberal usage of compression, saturation, and additive EQ (especially in the high frequencies), sibilance can quickly become a problem. Different voices have different tendencies, and combining a vocalist who generates an abundance of high frequencies with a microphone that was designed with an emphasis on capturing these same frequencies can result in a displeasing sound.

When air is generated and passes through, the resulting sound consists of mostly high frequencies. When I say bright, I’m referring to how the microphone reproduces high frequencies, specifically, “esses”.Įsses can be generated by a human voice when the tongue is placed on the upper palate, directly behind the top teeth. Some microphones do a better job of capturing and reproducing the rich, full, low frequencies of a voice, others are airy, silky, and articulate.Ĭontext is everything, of course, and whereas one of my favorite microphones, the AKG C414 XLII works like a dream on certain singers, I’ve found it to be overly “bright” on other performers. When recording the human voice, it’s essential to be mindful of how each of these components is working together. A typical sentence - whether its spoken or sung, is actually composed of several sonic components, some generated in the lungs and chest cavity, others a result of the resonance of the larynx (which we also refer to as our “voice box”), and even more that occur higher up in the anatomy (think tongue, lips, etc.)

The human voice is a wonderfully complex instrument.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)